What would an infrasonic track be doing on a netflix movie produced by Obamas Higher Ground Productions?

Can infrasound be used to harm people? Does infrasound cause physical changes while the sound impinges on the target? Why add it as a Separate Track instead of embedding it?

Infrasonic track in the “Leave the world behind” netflix Obama Movie.

It would be nice if this couple would qualify the frequency of the infrasound track so we can see what specific hertz its playing at. That would help target Why its being used.

Also:

“Infrasound can be used to investigate the internal structure of our planet, just like ultrasound is used for foetal scanning. Earthquakes produce very powerful seismic waves that can be classed as infrasound waves. Seismic waves from large earthquakes are detected around the world.”

Is this being used to probe the internals of they who watch that program while wearing their apple or android device to collect the feedback?

Can the infrasound ORDER the contents of the injections inside ones body?

Or is it just a way to add a fear trigger to “scary” movies to induce the watcher into a state of fear?

Heres an article that reviews how infrasound is used in horror movies.

<snip>

YOU’RE SITTING IN THE MOVIE theater; it’s pitch black except for the dim glow on-screen. Nothing scary has happened yet—but you see a person walking, alone. You feel an overwhelming sense of dread. A slow, growing hum murrs over footsteps, and you know the person isn’t safe. You, perhaps, feel you aren’t safe watching.

ATLAS OBSCURA COURSES

Learn with Us!

Check out our lineup of courses taught by world-class experts from around the world.See Courses

You wait for the inevitable conclusion, fixed on what you might see, listening for the cue that a killer or monster is ready to attack—though nothing on screen hints at this. The source for your anxiety is elusive, but it was carefully crafted through hidden audible elements that play on human emotions, causing your hairs to stand on end. This is the brilliance of what music does in a horror film.

The way composers make the most out of their musical tools to induce fear is both an art form and a science. Since horror movies rely on music, movie score composers carefully consider how to use familiar sounds in unusual ways; this distortion of reality unsettles us even if what we’re hearing is, in many ways, obscured.

“The sound itself could be created by an instrument that one would normally be able to identify, but is either processed, or performed in such a way as to hide the actual instrument,” says Harry Manfredini, whose music score for Friday the 13th was cemented in the thrasher film genre of the 1980s.

The sounds that do this to us aren’t always unusual; but their deep rumblings or high-pitched squeals signal danger almost (if not actually) instinctively. Distressed animal calls, women screaming and other nonlinear sounds, which are irregular noises with large wavelengths often found in nature, were used in The Shining and other movies to create an instinctual fear response, as recorded in the test subjects of a 2011 study at the University of California. Often these sounds are buried in the complex movie score or, sometimes, as subtle sound waves that give an adrenaline rush like a mini, internal roller coaster.

Taking a sound out of one normal context and then placing it into a new, scarier one can do this. While some of these sounds are subtle, others stick out so much they become characters themselves. People who have seen Friday the 13th learned that a specific sound (a human vocal noise described as “ki ki ki ma ma ma” by Manfredini) means that the killer, Jason Voorhees, is lurking nearby with his machete, even if he isn’t shown on screen. Just knowing that Jason might be in the room with us heightens our senses, and even though the sound is vocal, it’s unlike one any that a person would normally make. When Jason’s sound is isolated, you hear breathiness in an echo; but the surrounding music and bloody visuals work together, bringing the noise to a functionally creepy place.

One unsettling and hidden “sound” that is given credit for freaking out an audience is infrasound—a low-frequency sound that cannot be heard, but literally unsettles human beings down to our bones. Infrasound, which exists at 19 Hz and below, can be felt, but human ears begin to hear sound at 20 Hz. Infrasound exists in nature, and is created by wind, earthquakes, avalanches, and used by elephants to communicate over long distances. At a high enough volume, it may be possible for humans to perceive sound as low as 12 Hz, but even common objects can emit infrasound, something some horror movie music composers use to their advantage.

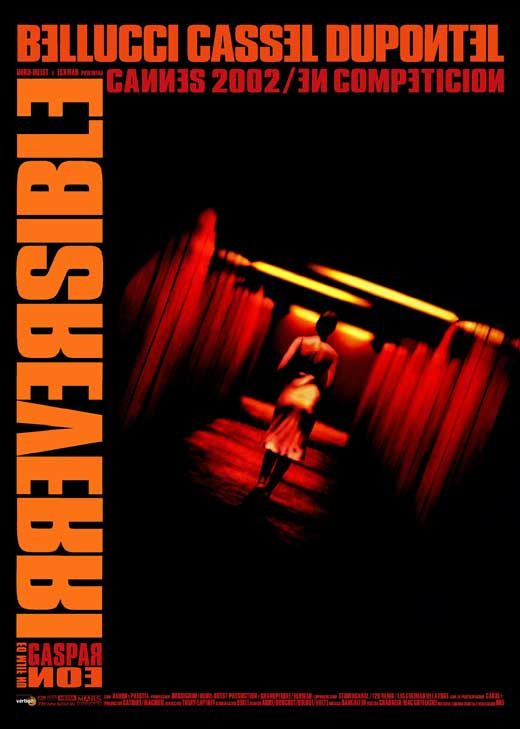

Filmmaker Gaspar Noe admitted in an interview that he intentionally used sound that registered at only 27 Hz, just above the 20 Hz limit for infrasound, in his 2002 film Irreversible. The movie is technically an avant-garde thriller, rather than classic horror—but the intense violence, raw camera angles and disturbing images and content have made it dip into the horror movie category. The characters embody the monster-side of human behavior and indulge; you’re bombarded with disturbing images of sexual violence, which understandably caused controversy, and the soundtrack intensifies this.

“You can’t hear it, but it makes you shake,” Noe told Salon. “In a good theater with a subwoofer, you may be more scared by the sound than by what’s happening on the screen.” In Irreversible, deep rumblings and a swaying, otherworldly grinding sound increases in volume, causing the viewer to feel dread just before extremely disturbing imagery begins. The 2002 movie Paranormal Activity was also rumored to use infrasound, though even if the deep rumblings in the film are above the 20 Hz threshold, they seemed to to a good job of unsettling audiences anyway.

Steve Goodman, in Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear, says that while the ways sound in media cause these responses in human perception are under-theorized, it likely has its place, especially with a source-less vibration like infrasound. “Abstract sensations cause anxiety due to the very absence of an object or cause,” he writes. “Without either, the imagination produces one, which can be more frightening than the reality.”

Sometimes using altered noises from everyday objects to get an infrasound-like effect can even save on production costs. Christian Stella, who mixed the score of the 2012 zombie film The Battery on a low budget, revealed on Reddit that he “ended up using recordings of power transformers, air conditioners, etc, that I modulated to make deeper.” Another part of the production team layered music on top of this to create the full movie score.

To manipulate the audience, Manfredini’s process begins with viewing a complete or at least near-complete film. To help the visual narrative along, he remembers the actions, objects or colors that reappear and creates audial themes around the visuals. Later, he overlays tones, rhythms and stand-out sounds to evoke something we’ve seen, sometimes using sounds as cues, to drive home the otherworldly narrative we find ourselves in while we clutch our seats. In a sense, he’s fooling the audience into believing that what we’re seeing is logical to the story we’re immersed in, and that we drew that conclusion first.

When he sees a scene where he thinks a special effect sound would work best, he works with the sound effects artist; then, he balances the effect sound with his score. “If his sound is a low sound, I might go high, and vice versa. Visually if I see something very large the logical choice would be a low sound, and if it is small, a high one,” Manfredini says. This is a departure from the horror movies of the 1940s and ‘50s, which relied on orchestral scores to fill in the silence. Horror movies today are more atmospheric, making the movie seem more plausible and causing a more direct sense of danger.

When we watch horror movies, we’re not meant to be simple spectators; we become passive participants. While immersed, we become convinced on some level that we’re there with the characters, walking around a dark corner or opening a door to a place we are definitely not meant to be. We might be safe in our living room while the monster approaches in the shadows, but the movie makes us believe otherwise. It’s just a trick of the ear, though, obviously. Hopefully.

<end snip>

Original URL here.

So sure it could just be to increase the level of fear one feels while watching the program but they have also made advances in how to use infrasound as a weapon.

I was able to find other references that infer this weaponized use:

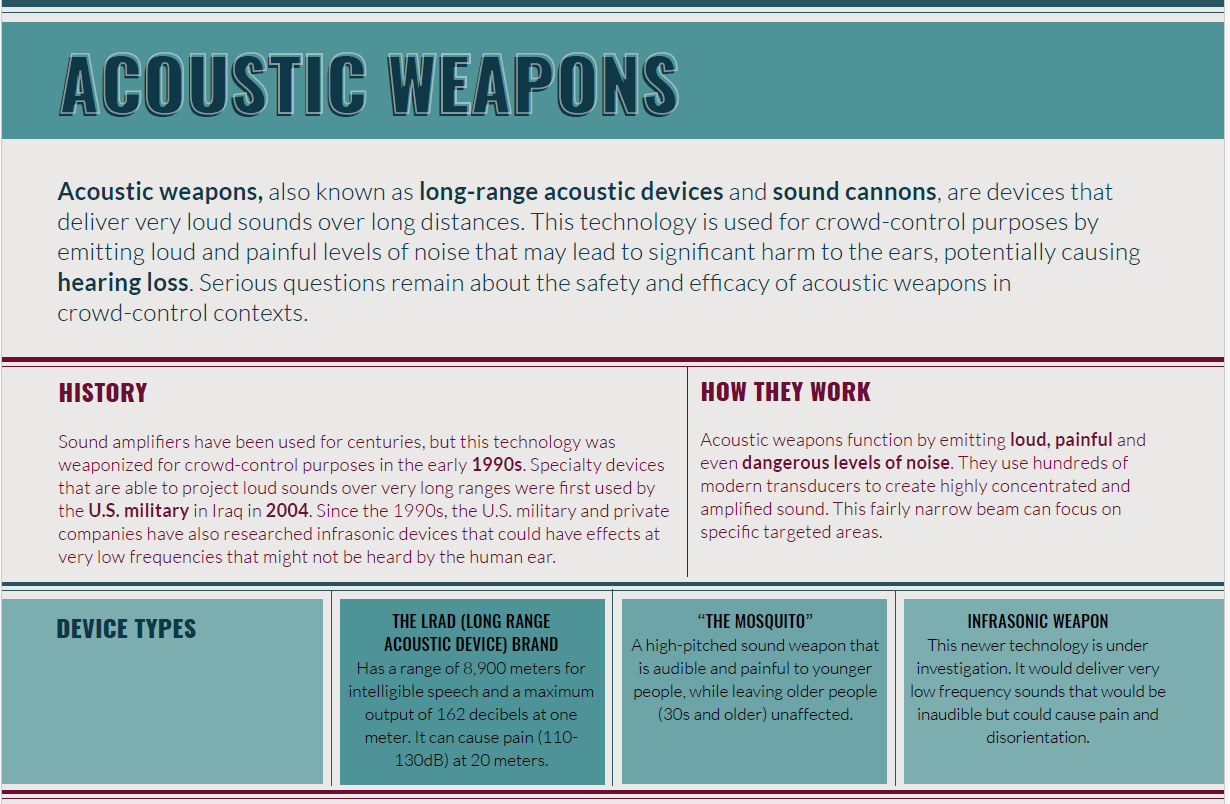

“INFRASONIC WEAPON This newer technology is under investigation. It would deliver very low frequency sounds that would be inaudible but could cause pain and disorientation. There is little medical literature on the effects of acoustic weapons on people.”

Quoted from this URL here.

What it does appear to indicate is that if people watch that film and then experience some sort of changed state or mood that its likely the program that is somehow inducing that in them.

I watched the film. It was not Scary to me. It was a little Funny. Since it was so apparently aimed at race baiting the viewers with the weird reverse racist commentary from the black girl. Both the Men in the film seemed to be decent and tried to trust each other in spite of the external events ongoing outside.

At no point was an Actual enemy combatant shown, just a couple remote shots of aircraft bombing the city on the other side of the harbor. There was also a drone aircraft that was supposedly dumping propaganda in arabic on that east coast location, while supposedly a similar drone had been seen in LA dropping pamphlets with Korean or Chinese language on it. But never any Troops or a direct hot war.

It did seem to be aimed at getting people to wait it out. Whatever IT is.

I came across this other article from Popular Science that reviews if sound can be used to kill. Its pasted in full below:

<snip>

Could A Sonic Weapon Make Your Head Explode?

Infrasonic sound can have very unusual non-auditory effects on the body. But does it kill?

BY SETH S. HOROWITZ | PUBLISHED NOV 20, 2012 9:00 PM EST

There’s an elevator in the Brown University Biomed building (hopefully fixed by now) that I’ve heard called “the elevator to hell,” not because of destination but because there is a bent blade in the overhead fan. The elevator is typical of older models, a box 2 meters by 2 meters by 3 meters with requisite buzzing fluorescent, making it a perfect resonator for low-frequency sounds. As soon as the doors close, you don’t really hear anything different, but you can feel your ears (and body, if you’re not wearing a coat) pulsing about four times per second. Even going only two floors can leave you pretty nauseated. The fan isn’t particularly powerful, but the damage to one of the blades just happens to change the air flow at a rate that is matched by the dimensions of the car.

This is the basis of what is called vibroacoustic syndrome—the effect of infrasonic output not on your hearing but on the various fluid-filled parts of your body.

People don’t usually think of infrasound as sound at all. You can hear very low-frequency sounds at levels above 88–100 dB down to a few cycles per second, but you can’t get any tonal information out of it below about 20Hz—it mostly just feels like beating pressure waves. And like any other sound, if presented at levels above 140 dB, it is going to cause pain.

But the primary effects of infrasound are not on your ears but on the rest of your body.

Because infrasound can affect people’s whole bodies, it has been under serious investigation by military and research organizations since the 1950s, largely the Navy and NASA, to figure out the effects of low-frequency vibration on people stuck on large, noisy ships with huge throbbing motors or on top of rockets launching into space. As with seemingly any bit of military research, it is the subject of speculation and devious rumors. Among the most infamous developers of infrasonic weapons was a Russian-born French researcher named Vladimir Gavreau. According to popular media at the time (and far too many current under-fact-checked web pages), Gavreau started to investigate reports of nausea in his lab that supposedly disappeared once a ventilator fan was disabled. He then launched into a series of experiments on the effects of infrasound on human subjects, with results (as reported in the press) ranging from subjects needing to be saved in the nick of time from an infrasonic “envelope of death” that damaged their internal organs to people having their organs “converted to jelly” by exposure to an infrasonic whistle.

By the time 166 dB is reached, people start noticing problems breathing.

Supposedly Gavreau had patented these, and they were the basis of secret government programs into infrasonic weapons. These would definitely qualify as acoustic weapons if you believe easily accessible web references. However, when I started digging deeper, I found that while Gavreau did exist and did do acoustic research, he had actually only written a few minor papers in the 1960s that describe human exposure to low-frequency (not infrasonic) sound, and none of the supposed patents existed. Subsequent and contemporary papers in infrasonic research that cite his work at all do so in the context of pointing out the problems of letting the press get hold of com- plex work. My personal theory is that the reason that his work survived even in the annals of conspiracy is that “Vladimir Gavreau” is just such a great moniker for a mad scientist that he had to be up to something.

Conspiracy theories aside, the characteristics of infrasound do lend it certain possibilities as a weapon. The low frequency of infrasonic sound and its corresponding long wavelength makes it much more capable of bending around or penetrating your body, creating an oscillating pressure system. Depending on the frequency, different parts of your body will resonate, which can have very unusual non-auditory effects. For example, one of the ones that occur at relatively safe sound levels (< 100 dB) occurs at 19Hz. If you sit in front of a very good-quality subwoofer and play a 19Hz sound (or have access to a sound programmer and get an audible sound to modulate at 19Hz), try taking off your glasses or removing your contacts. Your eyes will twitch. If you turn up the volume so you start approaching 110 dB, you may even start seeing colored lights at the periphery of your vision or ghostly gray regions in the center. This is because 19Hz is the resonant frequency of the human eyeball. The low-frequency pulsations start distorting the eyeball's shape and pushing on the retina, activating the rods and cones by pressure rather than light.* This non-auditory effect may be the basis of some supernatural folklore. In 1998, Tony Lawrence and Vic Tandy wrote a paper for the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research (not my usual fare) called “Ghosts in the Machine,” in which they describe how they got to the root of stories of a “haunted” laboratory. People in the lab had described seeing “ghostly” gray shapes that disappeared when they turned to face them. Upon examining the area, it turned out that a fan was resonating the room at 18.98Hz, almost exactly the resonant frequency of the human eyeball. When the fan was turned off, so did all stories of ghostly apparitions.

You would have to use a 240 dB source to get the head to resonate destructively. At that point it would be faster to just hit the person over the head.

Almost any part of your body, based on its volume and makeup, will vibrate at specific frequencies with enough power. Human eyeballs are fluid-filled ovoids, lungs are gas-filled membranes, and the human abdomen contains a variety of liquid-, solid-, and gas-filled pockets. All of these structures have limits to how much they can stretch when subjected to force, so if you provide enough power behind a vibration, they will stretch and shrink in time with the low-frequency vibrations of the air molecules around them. Since we don’t hear infrasonic frequencies very well, we are often unaware of exactly how loud the sounds are. At 130 dB, the inner ear will start undergoing direct pressure distortions unrelated to normal hearing, which can affect your ability to understand speech. At about 150 dB, people start complaining about nausea and whole body vibrations, usually in the chest and abdomen. By the time 166 dB is reached, people start noticing problems breathing, as the low-frequency pulses start impacting the lungs, reaching a critical point at about 177 dB, when infrasound from 0.5 to 8Hz can actually drive sonically induced artificial respiration at an abnormal rhythm. In addition, vibrations through a substrate such as the ground can be passed throughout your body via your skeleton, which in turn can cause your whole body to vibrate at 4–8Hz vertically and 1–2Hz side to side. The effects of this type of whole-body vibration can cause many problems, ranging from bone and joint damage with short exposure to nausea and visual damage with chronic exposure. The commonality of infrasonic vibration, especially in the realm of heavy equipment operation, has led federal and international health and safety organizations to create guidelines to limit people’s exposure to this type of infrasonic stimulus.

Ear-piercing sound

Since different body parts all do resonate and resonance can be highly destructive, could you build a practical infrasonic weapon by targeting a specific low-frequency resonance and thus not have to carry around a heavy amplifier or lock your victim in an elevator car? For example, imagine I am a mad scientist (a total stretch, I know) who wants to build a weapon using sound to make people’s heads explode. Resonance frequencies of human skulls have been calculated as part of studies looking at bone conduction for certain types of hearing aid devices. A dry (i.e., removed from the body and on a table) human skull has prominent acoustic resonances at about 9 and 12kHz, slightly lesser ones at 14 and 17kHz, and even smaller ones at 32 and 38kHz. These are convenient sounds because I won’t have to lug around a really big emitter for low frequencies, and most of them are not ultrasonic, so I don’t have to worry about smearing gel on the skull to get it to blow up. So how about if I just use a sonic emitter that puts out two peaks at the two highest resonance points, 9 and 12kHz, at 140 dB and wait until your head explodes? Well, it’ll be a while. In fact, it’s not likely to do anything other than possibly make a nice dry skull shimmy on the desk a bit, and it will do nothing to a live head other than make it turn toward you to see where that irritating sound is coming from.

I’ve always wanted to be able to run around blowing holes in things and chasing away supervillains.

The problem is that while your skull may vibrate maximally at those frequencies, it is surrounded by soft wet muscular and connective tissue and filled with gloppy brains and blood that do not resonate at those frequencies and thus damp out the resonant vibration like a rug placed in front of your stereo speakers. In fact, when a living human head was substituted for a dry skull in the same study, the 12kHz resonance peak was 70 dB lower, with the strongest resonance now at about 200Hz, and even that was 30 dB lower than the highest resonance of the dry skull. You would probably have to use something on the order of a 240 dB source to get the head to resonate destructively, and at that point it would be much faster to just hit the person over the head with the emitter and be done with it. So while we still cannot use infrasound to defend ourselves against dangerous severed heads and have not found the “brown sound” that would allow us to embarrass our friends, infrasound can cause potentially dangerous effects on living bodies—as long as you have a very high-powered pneumatic displacement source or operate in a very contained environment for a long time.

Sorry to be a spoilsport about sonic weapons. I’ve always wanted to be able to wire up a couple of speakers in my basement lab and run around blowing holes in things and chasing away supervillains, but most sonic weapons are more hype than hyper. Devices such as the LRAD exist and make effective deterrents, but even these have pronounced limitations. A handheld sonic disruptor will have to wait for some major breakthroughs in power source and transducer technologies. But the uses of sound in the future probably hold more interesting promise than the ability to destroy things.

* You can get a similar visual display, called phosphenes, by rubbing your eyes in a dark room.

Excerpted with permission from The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind by Seth S. Horowitz, Ph.D (Bloomsbury USA, 2012). Horowitz is a neuroscientist and former research professor at Brown University. He is the cofounder of NeuroPop, the first sound design and consulting firm to use neurosensory and psychophysical algorithms in music, sound design, and sonic branding. He is married to sound artist China Blue and lives in Warwick, RI. Buy The Universal Sense for $15 here.

<end snip>

Original URL here.

It seems any more technical review of infrasound as a weapon has been mostly removed from the internet.

It would be interesting to hear from people who are vaccinated and unvaccinated who watch “leave the world behind” to hear how they felt while watching it and shortly after. It made no nevermind to me and I’m unvaccinated.

Still it may be having an effect we don’t recognize, so we should be observant and see if anything evinces.

Stay Gray, Be Prepared, and Get ready for the Hot stage of WW3.